Action Versus Contemplation

Bridging the False Divide

One of the more quietly urgent debates of our time—particularly among those drawn to questions of meaning and the sacred—is whether we are called to act or to reflect. Is ours a moment that demands all-in political engagement, or are we in greater need of grounding ourselves in interior life and spiritual integrity?

On the one side is a group that says, "these are times that require an all-in engagement, we must fight for the very survival of democracy, there is no time to meditate." The other side maintains that having a center from which to respond to the current crisis is essential. “We must be a people of moral integrity with a spiritual core rooted in grace, peace, and love. That's the best way to respond to this challenge.”

I’ve met people on both sides of this spectrum and admire their conviction. But I disagree. This is not a choice. It is not an either/or dichotomy. In my view, there can be a both/and response. There can be both Action and Contemplation.

The 2018 book Action versus Contemplation: Why an Ancient Debate Still Matters, by Jennifer Summit and Blakey Vermeule, emerged from a college class taught at Stanford University. My brother gave me this book about a year ago, and as can be the case with me, I just got around to it.

For many, this act vs reflect seems a binary choice. But it needn’t be. Summit and Vermeule’s Action versus Contemplation: Why an Ancient Debate Still Matters suggests we are asking the wrong question. The real issue isn’t choosing between the two, but understanding how deeply interwoven they are—and always have been.

Summit and Vermeule, literature professors at San Francisco State and Stanford, respectively, trace the roots of this dichotomy through centuries of Western thought—from Aristotle's theoria versus praxis, to Cicero, Augustine, Francis Bacon, Hannah Arendt, and even Pixar’s A Bug’s Life. Their central claim: “The rhetoric of action and contemplation is nothing less than the unacknowledged medium of self-understanding in the modern world.”

What began as a university course has evolved into a wide-ranging intellectual survey of how we think about productivity, education, vocation, political activism, and purpose. Instead of resolving the tension between doing and thinking, the authors show how it continues to animate our lives in ways we may not realize.

A Longstanding Tension

For Aristotle, the highest good was Contemplation—“useless," in the utilitarian sense, but godlike in its detachment from material concerns. Yet even in ancient Greece, the contemplative life was made possible by political and economic action. Later thinkers refined the split: Augustine and Gregory the Great emphasized the need for both service and Contemplation; John Milton and Thoreau saw Contemplation as the more difficult, even heroic, form of human flourishing. The book walks us through this long history.

The ”act/reflect” tension plays out today in subtle ways: Should students pursue STEM or the humanities? Work for money or meaning? Is “work-life balance” real—or just a benefit of the privileged?

Politicians and public figures regularly touch this nerve. When Senator Marco Rubio once said, “We need more welders, less philosophers," he was echoing an old suspicion that Contemplation is indulgent and action is virtuous. But that framing, Summit and Vermeule argue, is historically contingent, not essential.

The authors point out that the studia humanitatis—the original humanistic disciplines—were once seen as practical, essential for civic leadership and public service. And science, now synonymous with pragmatism, began as a form of wonder.

The American Context

In our distracted, digitally saturated society, we often collapse Contemplation into mere inactivity. Americans may not work the most hours compared to other developed nations, but we do take the fewest vacations and frequently work while we are on those trips. We’re often too busy—or too tired—to ask whether we’re living well.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed that, if briefly. With millions confined to their homes, 2020 forced a confrontation with stillness. For some, this opened space for reflection; for others, it compounded hardship and anxiety. Either way, it underscored how difficult Contemplation has become in a culture obsessed with productivity and entertainment. That time was an anomaly, as we are now back to full throttle work mode.

Yet perhaps this is precisely the right time to revisit the classic fable of the ants and the grasshopper, which Summit and Vermeule explore throughout their book. In older versions, the hard-working ants survive the winter while the lazy grasshopper suffers. But newer adaptations—like A Bug’s Life—suggest a more nuanced story. Sometimes, the grasshopper sees a truth the ants have missed: that joy, art, and meaning matter, too.

Action, Contemplation, and Education

This debate shapes our educational system. American universities often ask students to choose between the “fuzzies” and the “techies”—between studying for the soul and training for a job. The authors push back against this false binary. Real education, they argue, should equip students to hold both aims together: to synthesize meaning and material well-being, soulcraft and success.

Yet the challenge is not just academic. In their roles as teachers, Summit and Vermeule see firsthand the “stress and relaxation” cycle that plagues students caught between career anxiety and existential yearning. Rather than offering easy answers, their book models a slower, more contemplative approach. It invites readers to see the ancient dialogue between thinking and doing not as a battle to resolve, but a conversation to join.

Among the most balanced voices in this tradition are those from within Christianity. Augustine wrote that no one should be so lost in Contemplation that they forget their neighbor, nor so consumed with activity that they forget God. Gregory the Great likened Contemplation and action to two eyes working together to see the world.

In the New Testament, the story of Mary and Martha often serves as a litmus test. Martha busies herself with hospitality, while Mary sits at Jesus’s feet. Jesus praises Mary—not for rejecting service, but for recognizing what was “most necessary” in the moment: presence.

This isn't an argument against action. Instead, it's a call to root action in something more profound. As the apostle Paul writes, "May the Lord make your love increase and overflow for each other and for everyone else" (1 Thess. 3:12). Contemplation deepens love for God; love for God overflows into love for others. The Christian tradition, then, offers a unique synthesis: not Contemplation versus action, but love that fuels both.

What the Book Offers (and Doesn’t)

Action versus Contemplation is not prescriptive. It does not offer five steps to a balanced life. Its structure, drawn from real-world teaching, is more mosaic than narrative. Some readers may wish for a more straightforward argument or a more practical application. Others will find that its open-ended nature is the point.

Rather than impose answers, Summit and Vermeule invite us to slow down. To examine what we mean by “meaningful work.” To question whether constant activity leads to a good life. To wonder whether our modern “rat race” is a deviation from human nature rather than a fulfillment of it.

What the authors do best is model contemplation—not in a monastery, but in conversation, literature, and classroom discussion. They recover forgotten threads of the Western tradition, showing that this is not just an elite intellectual concern, but a question each of us confronts when we ask: “What should I do with my life?”

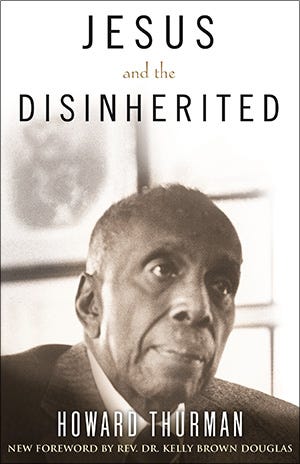

Action versus Contemplation is a book for our moment of crisis and reevaluation. Whether facing burnout, political upheaval, or the latest attack on democracy, many of us need a sustainable way forward. In the middle of the Civil Rights battles, Martin Luther King Jr ended up in a NYC hospital following a knife attack on him. Among the many visitors calling on King was Howard Thurman. The Boston University chaplain encouraged King to take time to recover, to re-center. King felt the call to action and resisted this advice at first, but later saw the wisdom. He took time off to heal, recover, and contemplate. Thurman's book, Jesus and the Disinherited, had accompanied King throughout the Civil Rights movement, and now its author provided the guidance that helped King continue.

In the end, the debate between action and Contemplation may be less about choosing sides and more about embracing wholeness. To think deeply is itself a kind of action. To act wisely demands reflection.

We don't have to be ants or grasshoppers. We might be both.

More to Come

James Hazelwood is a writer, photographer, and contemplative activist. www.jameshazelwood.net

We will be doing some family focus during August. See you in September.