Christmas Pageants and a Gritty Spirituality

How the Symbolic needs an Earthy Grounding to Serve our Soul

The hint half guessed, the gift half understood, is Incarnation.

Here the impossible union

Of spheres of evidence is actual,

Here the past and future

Are conquered, and reconciled,

T.S. Elliot

This excerpt from T.S. Elliot’s The Four Quartets caught my attention recently. The timing coincided with attending my wife’s congregation, where the annual Christmas pageant featured children dressed up as angels, a quirky-looking star of Bethlehem, and an abundance of nose-picking on the part of a few young shepherds. As many readers of these Notebook essays know, I lean strongly toward a symbolic and mystical understanding of Christianity. However, the danger from that point of view is that one can easily neglect the concrete, the body, and, indeed, the incarnation. Nose-picking at the birth of the eternal into the temporal just about captures the reality check needed.

One of the more earthy characters in the various Christmas stories who seems to be left absent from Christmas pageants is John the Baptist. Consider this epistle the beginning of a campaign to bring the fiery prophet cousin of Jesus into Christmas pageants. Come on, let’s “Make A Pageant Great Again.” John the Baptist is the wild man of the first few chapters of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. He’s the prophetic voice calling out in the wilderness. His early training in the monastic and ascetic communities of the Judean wilderness would have formed him in the Hebrew Bible writings of Isaiah and other prophets. John possibly belonged to the Essenes, a group of ex-Pats fed up with Jerusalem temple corruption and Roman occupation. They headed for the hills and formed an alternative community there. As is often the case in these hero journey tales, one person returns to bring the newly discovered wisdom back to the people from whence he or she came. John is doing that, preparing a way in the wilderness. He’s depicted as eating locusts and wild honey, wearing a leather belt, and bellowing out revelatory speech chastising amid a call for redemption. Later, of course, he’ll lose his head (literally) by threatening the powers that be.

Come on, people, let’s bring John into the Christmas pageants. Make him the chief nose picker coming down the aisle wielding an ax or winnowing fork, maybe a torch in the other hand, shouting out odes about repentance and the need for a change of heart, soul, mind, and society. I can see just about every fourth grader clamoring to play that role. There’d be a line out the door. What nine-year-old wouldn’t want a role filled with such disruptive passion? Quite possibly, there would be a call by church elders for safety and fire protocols as they witnessed an axe-wielding, flame-throwing nose picker trotting down the red carpet.

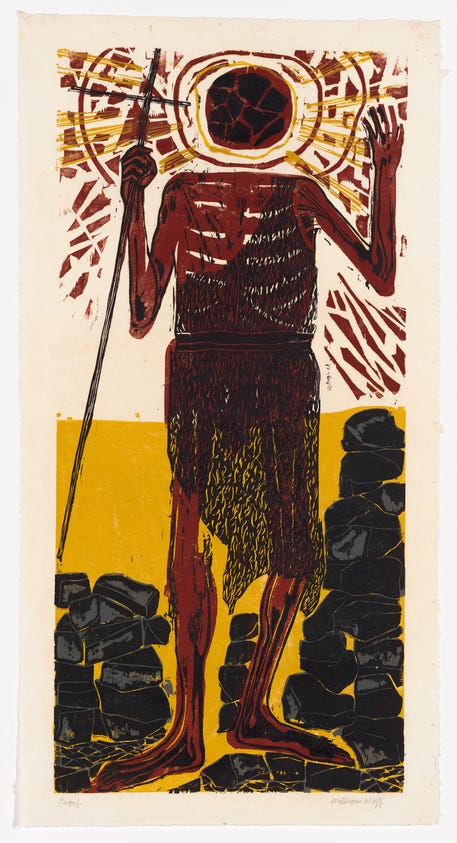

John the Baptist I, 1968, color woodcut, Courtesy of the estate of William F Wolff

You think a jest, and I do, at least about the axe and the flame thrower, but I think Christmas needs John the Baptist. Or, at a minimum, a more earthy and gritty manger scene. So often, the sacred nature of a hallmark-like greeting card barnyard seems to fall short. Have we failed to see the significance of Jesus being born in a manger, likely a cave directly attached to the humble dwelling of strangers in a so-called Inn? And even though the precise date of this birth is unknown, I can tell you from first-hand experience that the winter months are downright cold, possibly rainy, or even snowy in the hills around Bethlehem. This is not the Marriot.

Martin Luther drove the point home in his Christmas sermon around 1521. With the delightful grunt and grime theology he can be known for, Luther exposes the Incarnation with hay, manure, and barnyard critters. The paradoxical nature of something majestic happening in such an ordinary setting befuddled Luther. “If I had come to Bethlehem and seen it, I would have said: ‘This does not make sense. Can this be the Messiah? This is sheer nonsense.’ I would not have let myself be found inside the stable.” Luther continues, “Our God begins with angels and ends with shepherds.” I think the monk from Wittenberg would have cheered on the nose pickers from this past Sunday.

One of the great dangers of an overly spiritualized religious worldview is that it can become detached from reality. I have written extensively in three books about the need to recover a symbolic spirituality for our time. In my view, that is the central calling of religion for our time. But I know the symbolic must be grounded in something concrete. Otherwise, we can become pie-in-the-sky, naïve perpetrators of something disconnected from daily life. We need a gritty spirituality for our time.

If bringing a wild man like John the Baptist is not your cup of tea, let’s reengage with Mary. Yes, she is the Theotokos, Mother of the Divine Child, but we seem to have forgotten the qualities that make her a woman of strength and determination. We continue to opt for the sweet little pumpkin from Little House on the Prairie.

A Classic Icon of the Orthodox Church depiction of the Nativity. Read here for an explanation of the symbolism in the icon.

Joseph Campbell, the well-known 20th-century teacher of world mythologies, has pointed out the numerous ancient virgin birth narratives. The motif of a virgin birth appears in Greek mythology, Celtic tales, and Native American folklore, as well as in Buddhist traditions. A common theme involves a son born without a human father who then spends his life searching for his father.[1] This is all symbolic language for an internal human quest: the lifelong journey to find the pot of gold, the holy grail, or what we might refer to today as a place of wholeness or the human soul. It all begins with this miraculous birth.

And we need that birth to live in us.

We are all meant to be mothers of God. What good is it to me if this eternal birth of the divine Son takes place unceasingly, but does not take place within myself? And, what good is it to me if Mary is full of grace if I am not also full of grace? What good is it to me for the Creator to give birth to his Son if I do not also give birth to him in my time and my culture? This, then, is the fullness of time: When the Son of Man is begotten in us.[2]

Hans Urs von Balthasar, the 20th Century Swiss theologian

In the Eastern Orthodox communion, the Virgin Mary is given the title Theotokos (Θεοτόκος), a Greek word that means Birth-Giver to God, or God-Bearer, conferred by the Third Council of Ephesus in 431 CE. The most common modern translation is Mother of God. The Eastern Orthodox church calls her Panagia (all-holy) not because she is equal to God. Rather, they claim her as a supreme example of synergy, or cooperation, between God and humanity.

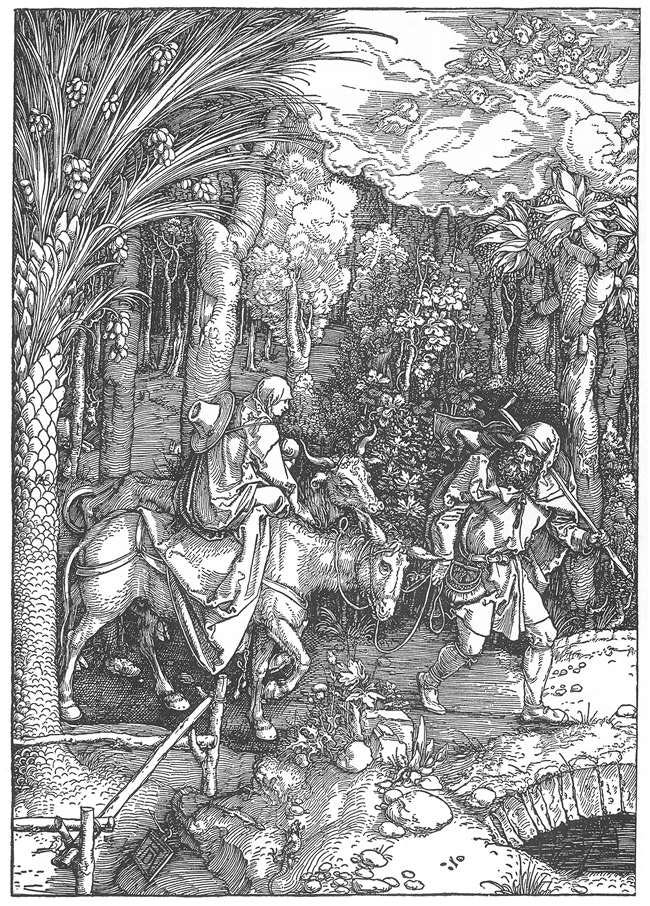

Albrecht Durer’s Flight to Egypt (1511)

Mary is depicted as a young mother, engaged, married, and betrothed to Joseph. In some narratives, they travel miles from Nazareth to Jerusalem, later as refugees to Egypt. They do so on foot, by donkey, or both, but certainly not in an Audi or an Uber. They retrace the steps of their ancestors, who wandered in the wilderness for 40 years. Mary embodies not just the innocence of a willing participant in the divine drama. She also does it with blisters on her feet. She’s giving birth in a cave-like barn sans epidural. We forget the grittiness and determination of the Theotokos in our greeting card industrial complex. Most of the women we’ve come to admire throughout history were sheer forces of nature. I imagine the young mother from Palestine the same way.

All I’m trying to do here is weave you back and forth between the symbolic and the mystical, with the ordinary stuff of life- the dusty roads and the place where placenta and nose-picking shepherds lay down together. Now, that’s a gritty spirituality.

Christmas is the perfect time to bring it all together. It is the impossible union of a moment, not just long ago but every moment when heaven and earth touch. And that touch changes us somehow; I don’t fully understand it, but I know in my heart it is real.

More to come,

P.S. Looking for a worthwhile charity to support this season of giving? Consider the Spitfire Club. “The Spitfire Club is a book club built around children's literature featuring strong, diverse, female protagonists. The Spitfire Club enhances literacy and social-emotional skills, nurturing love of reading, self, and fellow Spitfires across all communities.” Full disclosure: my daughter-in-law runs this non-profit in Alexandria, VA.

James Hazelwood is the author of books on spirituality and everyday life. His most recent collection of essays is Ordinary Mysteries: Reflections on Faith, Doubt and Meaning. His website is www.jameshazelwood.net

[1] Joseph Campbell, Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor, Novato, CA, New World Library, 2001, 62-65.

[2] Hans von Balthasar, Love Alone Is Credible, trans. D. C. Schindler, Ignatius Press, 2004, 42. This quote is often incorrectly attributed to Meister Eckhart, though Echart often used such imagery in his writings.

I love this, Jim! Have a great Christmas.

Thank you Elise