Escape from Freedom?

A Summary of Donald Kalsched's views of Inner Democracy

I know you just heard from me yesterday, but these ideas sprang forward early this morning.

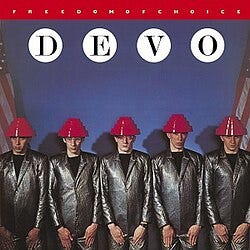

My music playlist has an option for various “radio” stations. Recently, I decided to venture down a nostalgic track of 70s and 80s Punk and New Wave music. Why? Who knows? Maybe it’s something I ate. But, in the course of a recent drive to Massachusetts, I heard the band DEVO, with their song Freedom of Choice, and the lyric, “Freedom of choice is what you got, freedom from choice is what you want.” The name of the band DEVO is short for de-evolution, which highlighted the band's critique of Western society's decline. But that lyric stuck in my head.

In the early 1940s, psychologist Erich Fromm wrote a book called Escape from Freedom. His main idea, though this is a bit of an oversimplification, is that people really don’t want choice. It’s too much effort, and because of our natural laziness, we prefer someone else to do the work for us. So, we go along and don’t fear; there’s always someone willing to step up and say, “I’ll make your lives easier and make all the decisions.”

“Freedom of choice is what you got, freedom from choice is what you want.”

All this came to mind as I read an article by Jungian psychologist Donald Kalsched, included in the book, Politics in a Traumatized World: Dystopia and the Creative Imagination. His essay, 'Inner and Outer Democracy and the Threat of Authoritarianism,' offers both a psychological and political reflection on democracy’s dangers and possibilities. His main point is that democracy must be understood not only as a system of government but also as a psychological and spiritual achievement. Fundamentally, democracy—whether in the inner life of the mind or in the outer life of society—requires the courage to face suffering, hold conflicting emotions, and embrace differences. Authoritarianism, on the other hand, occurs when individuals or nations cannot tolerate this tension and instead split, dissociate, and project—turning suffering into violence.

Inner vs. Outer Democracy and Authoritarianism

Kalsched describes his ideas around both an inner and an outer experience of democracy and authoritarianism. He’s helping us understand that the two realms are interconnected. Each of us has an inner governing system, and Kalsched is using this metaphor as a way of understanding what’s going on in our world and in our psyches.

Inner Democracy: “In a democracy, all the diverse parts are represented in a central ‘place’ that holds and contains the tension among these parts and keeps them in relation to each other. … In the inner world, it’s the central ego, and the tension that the ego is asked to hold is emotional tension among the parts of the self.”

Inner Authoritarianism: “In the trauma-work I do with individual patients, I have come to realize that I am frequently helping my patients to fight for a democracy of the psyche against the tyranny of an authoritarian inner system of defenses organized around existential fears and anxieties resulting from early trauma.”

Outer Democracy: “Democracy is best understood as a constant struggle for that freedom—a struggle against the inevitable threat of authoritarianism—a struggle that never ends.”

Outer Authoritarianism: “Authoritarian regimes or movements in the outer world can be thought of as externalizations—out-picturings if you will—of this inner authoritarian ‘system’ operating behind the scenes in the citizens of a stressed culture.”

I think this is where Kalsched brings the reality of what we are all experiencing into focus. It makes me wonder if DEVO was right—that we are at a point where the stress of modern society is causing us all to surrender. To use a trivial comparison, it’s like walking down the potato chip aisle at the grocery store. OMG. There is a whole aisle dedicated to chips. It’s overwhelming. I’ll grab the one I know, the familiar, or the one I remember from my past. That’s the appeal of nostalgia. Give me those Fritos from the 1970s. (insert link to trivial Fritos TV commercial)

The Problem of “Innocence”

One of Kalsched’s most original contributions is his analysis of innocence. He states that there are essentially two kinds of innocence, generative and malignant.

Generative innocence allows suffering and growth. It acknowledges that loss, pain, and wounding are a part of life, and learning how we integrate suffering into our souls can be helpful, or as he calls it, generative.

Malignant innocence denies responsibility and justifies violence.

As he writes, “Authoritarianism… justifies its violence in the name of an absolute form of innocence which is not allowed to suffer experience and indeed becomes a rationale for violence. Absolute innocence, trapped in the system (like a fly in amber) remains implicit, idealized, reified, and it becomes grotesque.”

This framework illuminates contemporary politics, where grievance culture thrives on fantasies and realities of violated innocence. “Grievances are usually built around inflated assumptions of one’s innocence and goodness—goodness that has been allegedly violated and needs to be avenged.”

Holding the Center - Can we do it?

Against these splits and projections, Kalsched points to leaders who embodied democracy’s deeper potential by holding the center in times of crisis:

Abraham Lincoln: “Approaching his second term, ‘with malice toward none, with charity for all.’ These individuals did not cater to the forces of fear and division. They held the center in their own suffering bodies and souls—and they paid a terrible price for it.”

Martin Luther King Jr.: King’s vision exemplified what Kalsched calls “democracy’s potential gift to us if we’re up for the emotional suffering that precedes the gift.”

Barack Obama: After the Charleston church massacre, Obama spoke of grace. ‘…out of this tragedy, God has visited grace upon us, for he has allowed us to see where we’ve been blind. … We may not have earned it, this grace… but we got it all the same; He gave it to us anyway.’ And then, Obama started to sing Amazing Grace, into the center of this fractured congregation and country.

These moments demonstrate what Kalsched calls the transformative suffering of democracy—the willingness to hold conflict and vulnerability rather than escape into grievance or violence.

Kalsched argues that democracy is constantly at risk because the human psyche resists suffering and looks for shortcuts—through violence, illusions, or grievances. However, democracy, both internal and external, is also the only way to achieve wholeness. As he states, “True democracy is a highly psychological institution which takes account of human nature as it is and makes allowances for the necessity of [inner] conflict.”

To preserve it, we must be willing to cry for our beloved country, to bear suffering rather than project it, and to hold the fragile center against the forces that would tear it apart.

More to Come,

James Hazelwood is an author and photographer, struggling to make sense of this world and his part in it. www.jameshazelwood.net

![Paperback Escape From Freedom 1st (first) edition by Erich Fromm published by Avon Library (1000-01-01) [Paperback] Book Paperback Escape From Freedom 1st (first) edition by Erich Fromm published by Avon Library (1000-01-01) [Paperback] Book](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!O6Av!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2a90a4f7-73e7-4847-ac36-e725d23eafcd_207x350.jpeg)