Shadows and Light:

The Inner Landscape of Photography

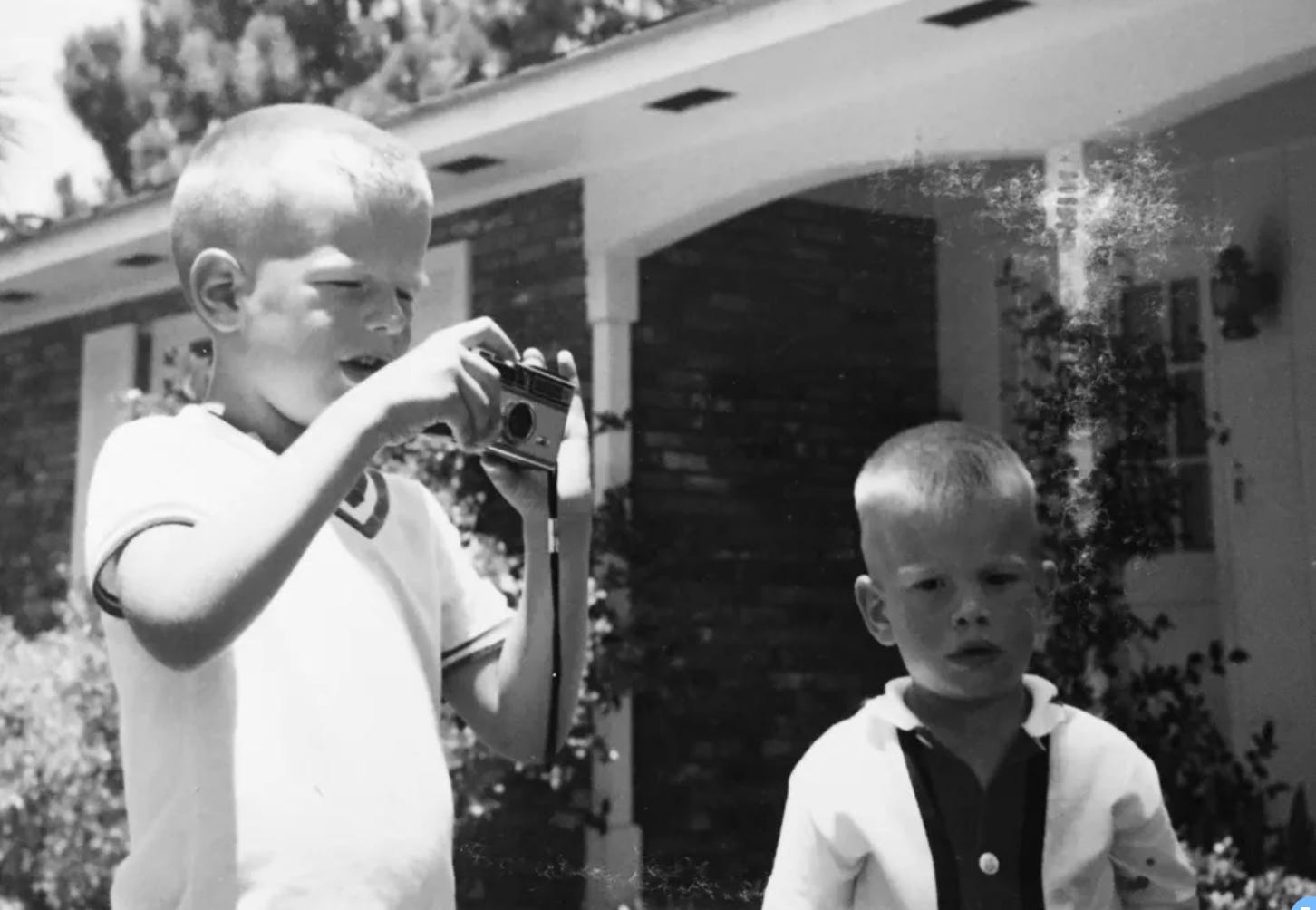

In 1975, I begged my father to drive me to Frank’s Highland Park Camera in Pasadena, California. I’d been saving up some money and had my eye on a Canon TLb, an entry-level 35mm film camera. I’m not sure of the origins of my interest in photography; perhaps it came from my parents, or an Ansel Adams print I had seen hanging in an office. Later, I commandeered a bathroom, turning it into a make-shift darkroom. You’d think my college degree and interest would have led me toward a career in photojournalism, but instead, it became an avocation. One I’m returning to at this next phase of life. (see my other Substack Newsletter on Photography)

Photography became ubiquitous—such a fitting word—with the advent of the iPhone. Now everyone has a camera ready. Images flood our feeds. Social media is filled with video clips, still photos, and the annoying reel. We’ve overwhelmed our ability to engage with symbols. Taking a moment to consider what photography truly is and how it can serve as a tool for a contemplative and meaningful life is worthwhile. So, let’s do just that.

Photography exists at the intersection of light and shadow, truth and illusion, presence and absence. This fundamental duality goes beyond technical issues like exposure and contrast—it touches on deep psychological and spiritual aspects of human experience. Through Carl Jung’s concept of shadow and light in the psyche, Joni Mitchell’s poetic meditation on these themes, and Susan Sontag’s critical analysis of photography’s nature, we can see how the photographic image becomes a mirror not just of external reality, but of our inner worlds.

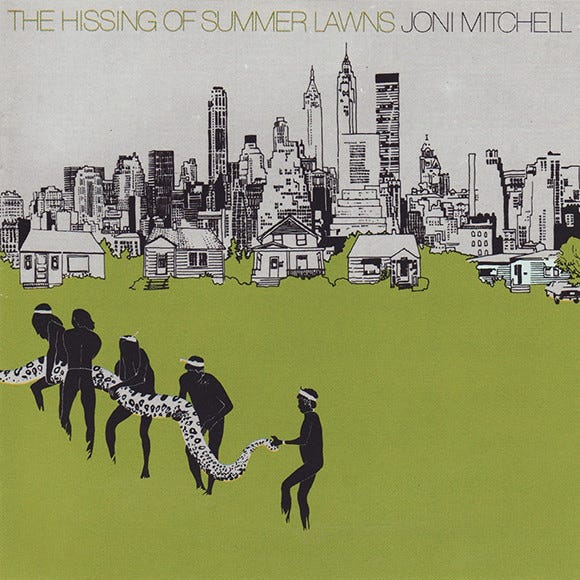

Joni Mitchell’s song “Shadows and Light” on her 1975 album, The Hissing of Summer Lawns, begins with a profound observation: “Every picture has its shadows / And it has some source of light / Blindness, blindness and sight.” These lyrics embody a truth that goes beyond the technical aspects of photography and into the realm of human consciousness itself. Just as no photograph can exist without the interplay of light and shadow, no human soul can exist without acknowledging both its bright and dark sides. In fairness to Mitchell, the song is not about photography but focuses on the relationship between personal freedom, love, and the consequences of pursuing one’s desires.

The Jungian Shadow and the Photographic Image

Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow refers to the unconscious parts of the personality that the conscious ego doesn’t recognize. The shadow includes repressed weaknesses, desires, instincts, but also creative potential and energy. Jung emphasized that achieving wholeness involves integrating the shadow instead of denying it—a process he called individuation. This psychological framework provides a strong metaphor for understanding photography’s dual nature.

A photograph, by its very nature, captures light and creates shadow. It displays certain aspects of reality while hiding others. The photographer’s choices about what to highlight and what to keep in the dark become unconscious acts of psychological projection. What we decide to photograph—and how we frame it—reveals as much about our internal world as it does about the external subject. The shadows in our photos may symbolize the “dark side” we deny, while the light emphasizes what we consciously value or want to show.

Mitchell’s lyrics continue this exploration: “Threatened by all things / Devil of cruelty / Drawn to all things / Devil of delight.” This recognition of humanity’s dual attraction to both darkness and light reflects Jung’s belief that the shadow isn’t entirely negative. Photography has also been drawn to both the beautiful and the terrible, the elevated and the abject. From war photography to portraits of suffering, and from glamour shots to documentation of decay, the medium covers the full range of human experience.

Susan Sontag’s Cave: Photography as Shadow Reality

Susan Sontag’s influential book “On Photography” begins with an essay titled “In Plato’s Cave,” intentionally referencing the ancient philosopher’s allegory about shadows on a cave wall being mistaken for reality. Sontag, who had a long-term relationship with photographer Annie Leibovitz, states that photographs act like these shadows—they are copies of reality, representations that we confuse with truth itself. In her analysis, photographs taken from reality provide images that influence our understanding, yet they remain fundamentally separate from the actual experiences they claim to depict. You’ve seen this at a recent concert where people seem more intent on filming with their phones rather than experiencing the event live.

Sontag’s critique reveals a spiritual dimension to the limits of photography. She contends that photos cultivate a voyeuristic connection to the world, allowing us to experience scenes and places without true engagement. This distance—this shadowy relationship with reality—diminishes our direct interaction with life. A photograph captures a single moment but removes its context, including the moments before and after, as well as the sounds, smells, and tactile sensations that give the experience depth. We are left with what Sontag calls “mere shadows of the truth.”

Yet Sontag also acknowledges photography’s unique power: unlike other art forms, photographs gain meaning over time and distance. Their surreal quality doesn’t arise from manipulation but from the passage of years, which transforms each picture into a memento mori—an alert to mortality and change. In this way, the shadows in photographs function as metaphors for memory itself—always present but incomplete and altered by time.

The Spiritual Dimension: Acceptance and Integration

Mitchell’s song features a key moment: an unknown voice softly says, ‘accept yourself.’ This pause, placed between lines about shadows and light, blindness and sight, hints that spiritual wholeness involves embracing the full picture—both what is shown and what remains hidden, both our light and shadow selves.

Photography, within this spiritual perspective, becomes a practice of observing and accepting. When we photograph with awareness, we recognize what is present without trying to mold reality into an idealized form. The shadows in our photos don’t need to be hidden or erased; they add depth, dimension, and sincerity. Great photographers understand this instinctively—they work with shadow instead of against it, knowing that contrast adds meaning.

The psychological task of integrating the shadow mirrors a photographer’s technical skill of balancing light and dark. Both demand courage to confront what has been hidden, patience to understand its significance, and wisdom to weave it into a cohesive whole. Just as Jung believed that wholeness arises from accepting all aspects of the self, photographic art often gains its greatest power when it refuses to sanitize reality, allowing shadows to reveal their truth.

Photographs serve both as mirrors and windows—they reflect our inner selves while also revealing the outer world. This dual purpose makes photography a uniquely powerful tool for psychological and spiritual growth. When we look at photographs, especially those we’ve taken ourselves, we see both the subject and our own perspective, both the world and our view of it. In this way, photography becomes not just a way to record reality, but a spiritual practice of seeing, accepting, and ultimately understanding what it truly means to be human.

And you thought you were simply taking a picture of a colorful salad to display on Instagram.

More to Come,

James Hazelwood is an author and documentary photographer. Yes, his website needs updating www.jameshazelwood.net