Bob Dylan’s Oh Mercy Album was released at the end of the 1980s after a string of flops. This recording became a bit of a renaissance for the man from Hibbing, Minnesota. Among the songs that seem relevant today is Political World. It’s a bit prophetic, as these 1989 lyrics could easily be written today.

A few stanzas to give you the idea.

We live in a political world

Where love don't have any place

We're living in times where men commit crimes

And crime don't have a faceWe live in a political world

Wisdom is thrown into jail

It rots in a cell misguided as hell

Leaving no one to pick up the trailWe live in a political world

Courage is a thing of the past

The houses are haunted, children aren't wanted

Your next day could be your lastHere's a link to the video; it’s a bit dated but if you don’t know the song, it’s worth a listen. Click here

We do live in a political world. Elections are commanding our attention worldwide as 2024 has witnessed people going to the polls in many parts of Europe, including Slovakia, France, and the United Kingdom. And then there is our US election, just one week away.

Engagement in the political world is a responsibility of citizenship. Indeed, one might even call it patriotic. I would. If we all abdicate this responsibility, there will always be nefarious forces and people hungry for power, wealth, and control. They will step forward and define the lives of others, turning them into subjects, not citizens. We have thousands of years of human history as evidence. At a minimum, we all need to vote!

But is there something underlying all this activity? Is it simply Get Out the Vote efforts, video marketing, and persuasion movements?

I recently revisited the little book Depth Psychology and a New Ethic by Erich Neuman. Years ago, it became one of the most influential reads of my life.

Neuman was Jewish and witnessed the horrors of World War II. He later moved to Israel early in that country's history and founded a school of Analytical Psychology. Much of his work delves into ancient history, religion, mythology, and anthropology. But his little book on a New Ethic addresses the social or political world.

Neuman distinguishes between an "old ethic," which pursued illusory perfection by repressing the dark side and he felt no longer viable. He was convinced that the deadliest peril now confronting humanity lay in the "scapegoat" psychology associated with the old ethic. We are in the grip of this psychology when we project our own dark shadow onto an individual or group identified as our "enemy," failing to see it in ourselves. The only effective alternative to this dangerous shadow projection is shadow recognition, acknowledgment, and integration into the totality of our individual and collective soul. Wholeness, not perfection, is the goal of the new ethic.

Neumann’s formulations call for both an individual and a cultural growth process that will enable the integration of the personal shadow and culturally shadowed “others." He knew firsthand the trauma of the Holocaust and the violent murder of his father by the Nazis. Yet, he encouraged people to move beyond the “old ethic” of projection with its accompanying vengeance towards a “new ethic” in which everyone takes personal responsibility for their decisions and actions. All in the hope that we would become more conscious of our shadow and, therefore, more mature and wise people.

Underlying Neuman’s work is Carl Jung’s concept of the human shadow. The idea can be abstract, but Robert Bly’s metaphor of the backpack can be helpful. In his A Little Book on the Human Shadow, Bly asks us to imagine that we each carry a backpack filled with the accumulations of life. Beginning as very young children where we are told to “keep still” or “it’s not nice to try and kill your brother or sister.” Later in High School, we may experience humiliation, mild, like someone poking fun at us in the locker room, to more severe events. Add to this the collective and communal struggles of life in our society. All this goes into the backpack; like many backpacks, you can’t see it when you wear it. It’s on your back. But it’s there inside us. Inside us individually as well as collectively.

You know your shadow has been activated when you strongly respond to an event, statement, person, speech, or political candidate. Like the other day, you heard something on the news or what a co-worker said in a meeting.

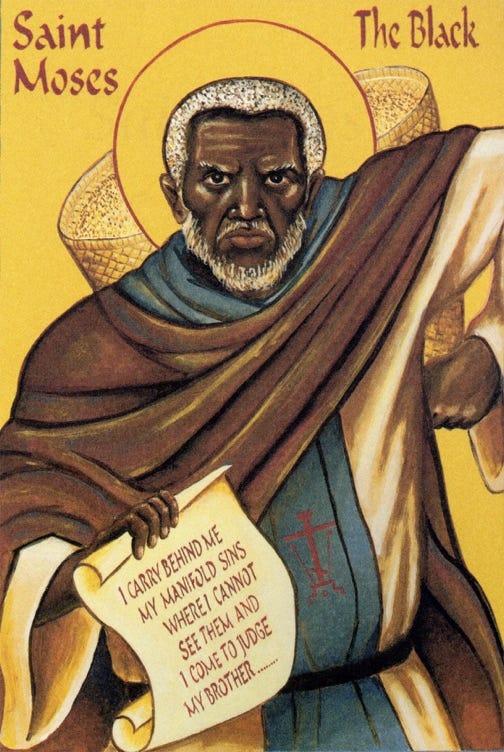

This backpack idea is a new language. In another era, we used more religious language. As an example, these words are from the fourth-century Christian monk, the venerable Moses, the Ethiopian of Scete, also known as the Black Moses. “I carry behind me my manifold sins where I cannot see them, and I come to judge my brother and sister…” Moses was an Ethiopian slave who led a life of crime before joining an Egyptian monastery committed to nonviolence. He founded a monastery of 75 monks. Talk about integrating your shadow.

I’ve been thinking about my backpack during this highly engaged and intense election season. While I’m clear on my choices for this election cycle, and in fact, I’ve already voted as my state allows that option. I’ve got real concerns about freedom, democracy, national security, and the Constitution. Those values have informed my choices. But I’ve also been rummaging around my backpack.

This week, words from historian Karen Armstrong came across my desk:

“The people we hate haunt us; they inhabit our minds in a negative way as we brood in a deviant form of meditation on their bad qualities. The enemy thus becomes our twin, a shadow self whom we come to resemble.” Karen Armstrong in Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life

I found myself taking a pause and realizing I’ve fallen into this trap of letting people, ideas, and images inhabit my mind and soul, and frankly, it’s been eating away at my soul. This is prompting some much-needed life adjustments. I’m hopeful these changes will help me both survive this election season and the likely messiness that will follow, as well as cause me to, well, frankly, be a better person – one who wrestles with his own shadow and backpack while engaging the times we live in.

What’s in your backpack? Jungian analyst Ann Belford Ulanov once offered this little exercise to help us. You can try it out if you wish to glimpse your own shadow. First, imagine a person of your gender whom you do not like. More than that, someone you despise, someone for whom the mere mention of their name churns up a strong reaction. You got that person in mind? Write down three or four, seven, ten, or twenty qualities about that person. That list! That’s a list of stuff in your backpack. That’s a list of your shadow qualities. Your first reaction may be, “This is ridiculous. I’m not like that at all.” I suggest you take this list to someone who knows you well and will be honest with you. Maybe a spouse, a partner, or a close friend. My guess is, if they are honest, they’ll probably respond, “Well, if you want me to be honest with you, yes, I have seen that side of you.” Maybe they can even help you with a story about a time when they saw you fully exposed.

So, how does all this relate to politics? I once heard an interview with the singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell. She responded, “The lessons we learned on the playground are the same lessons that get applied to our lives as adults, and even beyond to the realm of global affairs.”

Much of the unrest, division, and vitriol we see today might be a manifestation of our collective backpacks. We are blaming ‘those’ people for our problems. The word ‘those’ is different depending on your perspective. Over the last ten years, because I’ve sat with many people from a variety of backgrounds, racial compositions, economic settings, and political persuasions, I’ve heard ‘those people’ described as immigrants, liberals, young people, old people, republicans, democrats, blacks, whites, poor, rich, etc. There is a lot of fear and woundedness behind all the energy used in those conversations.

“Why do you see the speck in your neighbor's eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye? Or how can you say to your neighbor, 'Let me take the speck out of your eye' while the log is in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor's eye."

(Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount Matthew 7:3-5).

Knowing all this should not be interpreted as avoiding activism and engagement in the political process. I’ve been active in various get-out-the-vote efforts in the US for multiple election cycles. It does mean that I am best when I bring an understanding of my shadow to the engagement. It tempers my reactivity when I hear or read something I find outrageous. Rather than an impulsive response, I’m forced to step back and ask questions, perhaps pursue further investigation. I can still emerge with a clear and forceful response. But it’s now a response rooted in something deeper. At least, that’s my hope.

It's also a hope for our collective society in these divisive times.

+

More to Come,

James Hazelwood is an author and photographer who reflects on the intersection of the spiritual with the everyday ordinary aspects of life. His website is www.jameshazelwood.net

Thank You! This is a beautiful way to look at our lives in comparison with others and how we can improve our thinking and judging others. Blessings! Roberta Briggs

In the 19th Century there was a book out of LC-MS "Law and Gospel" by a Professor Walter. There is not grace without law and law without grace is judgment. Freud and Young came later. Whether helping out those in grief or general counseling or listening to a sermon, I often wonder where is the darkness? It loves to hide in our psyches or the "happy slappy" of just praise worship or in our blame projections of others. This is a wonderful article in my opinion as it keeps the issue of "the shadow" in front of the readers. It is our personal shadows that are forgiven, things known and unknown. It is a personal issue, a family issue and a national issue with lies at the center. Pastor Don Marxhausen, Retired.